Awareness of Belief

Abstract

Mindreading and Interpretation

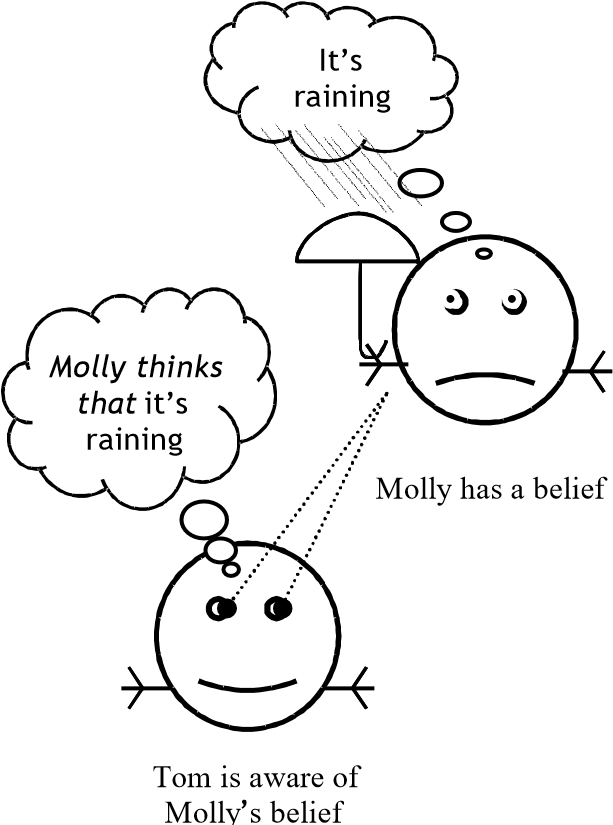

An awareness of other people’s

beliefs plays an essential role in everyday life. In this diagram, for

example, Molly believes that it’s raining, and Tom is aware of her

belief. But what is ‘awareness of belief’? What is involved in being

able to recognise and think about beliefs? Here are two

requirements:

An awareness of other people’s

beliefs plays an essential role in everyday life. In this diagram, for

example, Molly believes that it’s raining, and Tom is aware of her

belief. But what is ‘awareness of belief’? What is involved in being

able to recognise and think about beliefs? Here are two

requirements:

Variation Requirement Being aware of beliefs involves appreciating how different people may have beliefs different from one’s own (including beliefs which are inconsistent with one’s own beliefs).

Truth Requirement Being aware of beliefs involves understanding what it is for beliefs to be false.

Are these different requirements, in the sense that someone could satisfy one without satisfying the other? No one could meet the Truth Requirement without meeting the Variation Requirement, because understanding that a belief is false involves realising one should not believe it and appreciating the possibility of having other beliefs in its place. But could someone meet the Variation Requirement without meeting the Truth Requirement? In other words, is it possible to be aware of beliefs which are inconsistent without being aware that at least one of these beliefs is false?

For instance, suppose Tom thinks it isn’t raining, and suppose he is aware of this belief and of Molly’s belief that it is raining. One of these beliefs must be false: either Tom or Molly has a false belief, so Tom is aware of a belief that is false. But does it necessarily follow that Tom can understand that one of these beliefs is false?

Some philosophers say ‘yes’, others say ‘no’. Donald Davidson would say ‘no’, because he thinks that being aware of a belief involves being able to appreciate the possibility of false belief. In fact, Davidson thinks that merely having a belief requires understanding that it may be false. He says, “one cannot believe something, or doubt it, without knowing that what one believes or doubts maybe either true or false, and in particular, that one may be wrong” (Davidson 1999: 12).

Opposing Davidson’s view, Daniel Dennett claims that it is possible to be aware of another person’s beliefs without understanding that beliefs can be false.1 As Dennett describes it, being aware of beliefs doesn’t require having any concepts at all. Instead, being aware of beliefs is a matter of being systematically sensitive to another person’s beliefs in a range of practical ways (Dennett 1978: 275; 1987: 247). For example, purposefully engaging in deception would be a practical way of showing an appreciation of potential differences in belief. So Dennett denies, whereas Davidson accepts, that awareness of belief necessarily involves understanding that beliefs can be false.

Davidson and Dennett also have different views about why awareness of beliefs matters. For Dennett, the point of our being aware of other people’s beliefs is to co-ordinate social interaction (see Dennett 1987: 50). On the other hand, Davidson regards our capacity to be aware of others’ beliefs as an essential part of understanding objects and events as inhabiting a world shared by all but independent of any one person. For Davidson, awareness of belief is defined by its role in enabling us to grasp that objects and events are mind-independent, rather than by its role in facilitating social interaction (Davidson 1991b: 201; 1991a: 164). This disagreement is relevant because if coordinating social interaction is what awareness of belief is for, then there is no reason to think it requires understanding the possibility that beliefs can be false. Since everyone acts on her own beliefs and modifies them in the light of evidence available to her, it is irrelevant whose beliefs are false from the point of view of co-ordinating interaction. All that matters are differences in belief.

Who is right? Why is it important that we are aware of others’ beliefs, and does this awareness require that we understand what it is for beliefs to be false? The aim of this paper is to argue that there are two varieties of awareness of belief, which I’ll call ‘mindreading’ and ‘interpreting’. Instead of seeing Davidson and Dennett as saying conflicting things about a single kind of awareness of belief, I think they are better understood as talking about different kinds of awareness. Here is an initial characterisation:

Mindreading involves being sensitive to which beliefs a person has, and knowing which actions her having these beliefs should lead to. A mindreader knows how beliefs are acquired and what practical consequences they have for action.

Interpreting involves using beliefs in giving reason-explanations. An interpreter knows why someone should have particular beliefs, and why these beliefs should lead to certain actions.

Are mindreading and interpreting really different? Most people probably think there is just one kind of awareness of belief, and would assume that my initial characterisations of mindreading and interpretation simply emphasise different aspects of a single ability. In this paper, I aim to make the distinction between mindreading and interpretation theoretically viable, and to argue that interpreting beliefs, but not mindreading them, necessarily involves understanding that beliefs can be false. Someone who mindreads beliefs will satisfy the Variation Requirement but not the Truth requirement, whereas interpreting beliefs involves satisfying the Truth Requirement. So whether it is possible to be aware of differences in belief without understanding what it is for a belief to be false depends on whether we are talking about mindreading or interpretation.

What is it for a belief to be true or false? Pragmatists and Intellectualists

My question is whether being aware of differences in people’s beliefs involves understanding that beliefs can be false. This question has two moving parts: an answer depends both on what awareness of belief is, and on what it is for a belief to be true or false.

We can’t take the notion of truth for granted, because there is much disagreement about it. One major axis of disagreement is that between Pragmatists and Intellectualists. William James, a Pragmatist, explains the point at issue:

“Truth … is a property of certain of our ideas. It means their ‘agreement’, as falsity means their disagreement, with ‘reality’. Pragmatists and intellectualists both accept this definition as a matter of course. They begin to quarrel only after the question is raised as to what may precisely be meant by the term ‘agreement’” (1907: 76).

I’ll describe the Pragmatist’s position first. In “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”, Peirce explains the Pragmatist’s position roughly as follows.2 Accepting a belief establishes ‘habits’, which are dispositions to think and act in various ways in different circumstances. Any belief can be distinguished by the particular habits established by its acceptance. Furthermore, the whole purpose of accepting a belief is to establish these habits: “whatever there is connected with a thought, but irrelevant to its purpose, is an accretion to it, but no part of it.” So, the Pragmatist infers, “To develop [a belief’s] meaning, we have, therefore, simply to determine what habits it produces, for what a thing means is simply what habits it involves.” In other words, the Pragmatist holds that the content of a belief is exhaustively determined by which habits accepting it would establish. This is a form of functionalism about belief.

This account allows the Pragmatist to define what it is for a belief to ‘agree’ with reality in terms of the habits associated with it. Thus James, presenting a view he regards himself as sharing with Peirce, says:

“Pragmatism defines ‘agreeing’ to mean certain ways of ‘working,’ be they actual or potential. Thus, for my statement ‘the desk exists’ to be true of a desk recognized as real by you, it must be able to lead me to shake your desk, to explain myself by words that suggest that desk to your mind, to make a drawing that is like the desk you see, etc” (James 1911: 218; cf. 1907: 82, 1911: 191).

But exactly which ways of working constitute the agreement of an idea with reality? The Pragmatist answers that when an idea works in a way that is consistently beneficial to a thinker, the idea agrees with reality and is therefore true. So, for the Pragmatist:

“Those thoughts are true which guide us to beneficial interaction with sensible particulars as they occur.”3

The Pragmatist’s claim isn’t just that true beliefs happen to ‘guide us to beneficial interaction’, or that beneficial beliefs are likely to be true; anyone can accept this. Rather, the Pragmatist is claiming that this is what it means for beliefs to ‘agree’ with reality.4

Where James talks about the agreement of a belief with reality, modern Pragmatists like Ruth Millikan or David Papineau talk about the truthconditions of beliefs. Like Peirce and James, they regard beliefs as having characteristic consequences for thought and action. They also hold that the consequences of a belief can be judged successful or unsuccessful without reference to the truth of that belief. Although different Pragmatists use different notions of success, the basic idea is that an action is successful if it fulfils the agent’s intention in acting, and a belief is successful if it would lead to successful action. Given these claims, the Pragmatist asserts that:

(P) The truth-condition of a belief is that condition under which actions that result rationally from the belief will normally succeed.

How does this work? Suppose we know that Molly has a particular belief, S, and that we know which actions this belief causes, but that we don’t know which truth-condition her belief has. The Pragmatist’s claim is, in effect, that a generalisation of the form:

(G) All actions that are rational consequences of Molly’s belief S will succeed if and only if p

is equivalent to a statement of the form:

(T) Molly’s belief S is true if and only if p

In general, the Pragmatist claims that a belief’s truth-condition can be defined as whatever condition is required for the success of all actions reasonably caused by that belief.5 This is a contemporary reformulation of James’ claim that a belief agrees with reality to the extent that it leads to beneficial actions.

The Intellectualist objects that the Pragmatist gets things exactly the wrong way around. Whereas the Pragmatist defines the truth-condition of a belief in terms of its consequences, the Intellectualist claims that the truthcondition of a belief explains which actions someone who acts on that belief should perform. For example, imagine it’s raining and Molly takes an umbrella because she wants to stay dry. The Intellectualist claims that we can explain why Molly should take an umbrella in terms of the fact that she believes that taking an umbrella will keep her dry. So the Intellectualist treats the following explanation as a paradigm:

(I1) Molly believes that taking an umbrella will keep her dry.

(I2) Molly wants to stay dry.

∴ (I3) Molly should take an umbrella.

As the Intellectualist understands it, this isn’t a prediction of what Molly will actually do; rather, justifies Molly’s taking an umbrella. The Intellectualist asks why Molly’s belief should cause her to take an umbrella, rather than to call a taxi or stay at home. Her answer is that Molly’s belief should have this consequence because it is the belief that taking an umbrella will keep her dry.

In general, the Intellectualist claims that the truth-condition of a belief explains which actions that belief should result in. So knowing what a person believes gives us insight into why she acts, and this insight is not reducible to knowing which normal consequences her beliefs have. This is incompatible with the Pragmatist’s way of defining truth-conditions for beliefs, because the Pragmatist defines the truth-condition of a belief as whatever condition guarantees the normal success of actions that are rational consequences of that belief. So the Pragmatist’s explanation works in the opposite direction:

(P2) Molly wants to stay dry.

(P3) Molly should take an umbrella.

∴ (P1) If Molly has a belief, S, which causes her to take an umbrella, then S is the belief that taking an umbrella will keep her dry.

The Pragmatist wants to explain why Molly’s belief is true if and only if taking an umbrella will keep her dry. The Intellectualist, on the other hand, wants to explain why Molly’s having this particular belief makes it the case that she should take an umbrella if she wants to stay dry. The Pragmatist and Intellectualist positions are opposed because these two explanations can’t be combined.

So the Pragmatist’s argument with the Intellectualist concerning the nature of truth boils down to a question about the direction of explanation. The question is, Do the reasonable consequences of a belief determine its truthcondition, or are they determined by its truth-condition? Put like this, the debate between the Pragmatist and the Intellectualist seems to be not at all relevant to my theme, which is awareness of belief. So why does it matter?

Pragmatist mindreaders and Intellectualist interpreters

To answer this question, we need to change our focus from considering what it is for a belief to be true or false to considering what it is to think of a belief as true or false. The Pragmatist and the Intellectualist present themselves as giving philosophical accounts of what it is for a belief to be true or false, but in this section I’ll argue that we can reinterpret them as giving accounts of what it is to be aware of beliefs as true or false. The Pragmatist is, in effect, giving an account of what mindreading is, while the Intellectualist is giving an account of interpreting.

I’ll start with an analogy to illustrate how the argument is going to work. Instead of beliefs, think about maps. Imagine using a map to find out where Bielefeld University is. Knowing how to use the map involves being able to look at the map and the landmarks around one in order to decide which way to walk. In addition to knowing how to use maps, most of us probably also know why they work, that is, why they can be used to find out where to walk. Maps work because they represent our environment, and inaccurate maps can mislead us because they misrepresent our environment. Knowing why a map works enables us to justify the use we make of it to select a route to the university: the map’s representing our environment justifies us in using the map to decide where to walk.

Just as the Pragmatist explains what it is for a belief to have a particular truth-condition, so she can give an analogous account of what it is for a map to represent a particular place. In the case of beliefs, the Pragmatist identifies the truth-condition of a belief as that condition under which actions rationally based on it normally succeed. In the case of maps, the Pragmatist says that a map represents that place in which using the map appropriately will normally get you where you want to be (compare Dewey 1938: 402-3).

So, for instance:

(R*) This map represents* Bielefeld if and only if following the map appropriately will normally get you wherever you want to be in Bielefeld.

This gives us a notion of representation for maps, which I’ll call ‘representation*’. Is representation* the same as our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of representation? Two things might make it seem plausible that it is:

If following a map doesn’t normally get us where we want to be in Bielefeld, then it can’t represent Bielefeld.

If following a map normally gets us where we want to be in Bielefeld, then it must represent Bielefeld.

This shows that a map represents Bielefeld if and only if it represents* Bielefeld. However, the two notions of representation are different. This is because they play different roles in justifying our use of maps. Suppose we meet someone who knows how to use maps to find her way around, but doesn’t understand why following a map gets her where she wants to be. For her, the map is a kind of magic, or else she treats it as a brute fact that maps can be used to navigate. Using our pre-theoretic notion of representation, we can explain to her that the usual way of following the map should get her where she wants to be because the map represents Bielefeld. However, our explanation would be circular if we used the Pragmatist’s notion of representation*. For to say that the map represents* Bielefeld is just to say that a particular way of following the map will to get us where we want to be. So we can’t explain why following the map gets us where we want to be in terms of the Pragmatist’s notion of representation*. This shows that representation is not the same as representation*.

Now imagine someone who doesn’t understand our ordinary, pretheoretic notion of representation, but does grasp the Pragmatist’s notion of representation* for maps. This person is a practising Pragmatist with respect to maps. She would be able to distinguish an incorrect from a correct map, but she would not be able to explain the usefulness of a map in terms of its representational properties. She would know how to use maps to navigate, but she wouldn’t know why they get her to where she wants to be. She can mindread maps but not interpret them.

There is an analogous argument concerning the Pragmatist’s account of truth-conditions for beliefs. Here is how the Pragmatist’s defines the truthcondition of a belief again:

(T*) The truth*-condition of a belief is that condition under which actions that result rationally from the belief will normally succeed.

I’ve called what the Pragmatist defines truth* so that we can ask whether truth* is like our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of truth for beliefs. Assume, for the sake of argument, that a belief is true* under exactly the same conditions that it is true.6 Even on this assumption, truth* is not the same as truth. This is because we use the notion of truth in some explanations of thought and action in which the notion of truth* can’t feature.

The example I gave earlier illustrates this. In the example, it’s raining and Molly wants to stay dry whilst she’s out and about. Molly has a belief that is true if and only if taking an umbrella will keep her dry. This belief of Molly’s causes her to take an umbrella. But why should this belief of Molly’s cause her to take an umbrella? Why shouldn’t this belief instead cause her to call a taxi or wear an anorak? Why aren’t these rational consequences of Molly’s belief? Intuitively, there is a simple answer to this question. Molly’s belief should cause her to take an umbrella because it is the belief that taking an umbrella will keep her dry. Which truth-condition Molly’s belief has explains why her having this belief should result in certain actions and not others. But the truth*-condition of Molly’s belief can’t explain why this belief should cause her to take an umbrella. This is because which truth*-condition Molly’s belief has is determined by which actions it should cause. So you can’t use truth*-conditions to explain why something is a rational consequence of a belief.7

This is the difference between the notions of truth and truth*. The notion of truth can explain why particular beliefs should result in certain actions. The notion of truth* can’t do this, because its definition has already assumed the relevant facts about which actions a belief should result in. You can’t use a concept to explain something you have already assumed in defining that concept.8

We don’t ordinarily think about truth in the way described by the Pragmatist. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the Pragmatist describes a perfectly coherent way of thinking about beliefs. Imagine someone who doesn’t understand our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of truth for beliefs, but does understand the Pragmatist’s notion of truth*. I don’t mean to suggest that this person reflectively adheres to the Pragmatist’s philosophical claims about truth*; rather, the Pragmatist’s theory describes how this person actually thinks about beliefs in practice. She is a practising Pragmatist with respect to beliefs.

The practising Pragmatist can appreciate that not all beliefs are true*, and she can appreciate that different people may have different beliefs. She also knows how beliefs work; that is, she knows under what conditions beliefs are acquired, and what practical consequences beliefs tend to have for action. Nevertheless, she doesn’t understand why beliefs have the consequences they do. She can’t justify her own or other people’s actions in terms of the truth*-conditions of their beliefs. If we assume (with the Intellectualist) that one of the functions of the concept of truth is to play this role, we can say that she doesn’t really understand what it is for a belief to be true, even though she is aware of beliefs. This entails a qualified answer to the question I started with: unless the Pragmatist is right about truth, a practising Pragmatist satisfies the Variation Requirement but not the Truth Requirement. And, irrespective of who is right, the Pragmatist and Intellectualist accounts of truth can be reinterpreted as theoretical descriptions of two kinds of awareness of belief. Mindreading is the activity of thinking about beliefs as if one were using the Pragmatist’s account of truth*, and Interpretation is thinking about beliefs in terms of the Intellectualist’s notion of truth. Mindreaders are Pragmatists; interpreters are Intellectualists.9

Notes

In “Conditions of Personhood” (in Dennett 1978), he asserts that ‘taking the intentional stance’ towards another person does not require reflective understanding of what one is doing.

“How to Make Our Ideas Clear” is reprinted in Peirce (1932).

James (1911: 82); cf. Peirce (1932: 247/5.387): “truth … is distinguished from falsehood simply by this, that if acted on it should, on full consideration, carry us to the point we aim at and not astray.”

James (1911: 154); cf. (1911: 219-220) and (1911: 273).

Papineau (1993: §3.7.v), (1993: §3.9) and Millikan (1984: 77), (1993: 72-73). I am ignoring these authors’ many refinements of the Pragmatist’s basic claim.

This is a point on which many arguments against pragmatism concentrate. Some argue that the Pragmatist’s account yields intuitively wrong (Pietroski 1992) or non-realist truth-conditions (Forbes 1989; Peacocke 1992, §5.2). Even if the Pragmatist can answer these objections, this doesn’t show her account of truth is adequate.

Some philosophers present this kind of point as an objection to the Pragmatist’s account of truth (Godfrey-Smith 1996: §6.3; Johnston 1993), without mentioning that some pragmatists explicitly endorse it as a consequence of their theories (James 1907: 85; Millikan 1993: 237).

For people who would object to this sentence, see the replies to Johnston (1993) by Wright (1992, 130), Miller (1995), (1997), and Menzies and Pettit (1993). These objections can be bypassed, because my argument requires only that an explanation looses some of its justificatory depth if it uses a concept to explain something already assumed in defining that concept.

I have been helped enormously by comments and criticisms at GAP4, and by many other people.

References

Bennett, Jonathan

1991 “How To Read Minds in Behaviour” in Andrew Whiten (ed.) Natural Theories of the Mind: evolution, development and simulation of everyday mindreading, Oxford: Blackwell

Davidson, Donald

1991a “Three Varieties of Knowledge” in A. Griffiths (ed.) Memorial Essays for A. J. Ayer Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, Cambridge: University Press

1991b “Epistemology Externalized”, Dialectica vol. 45, no. 2-3

1999 “The Emergence of Thought”, Erkenntnis 51 Dennett, Daniel

1978 Brainstorms: philosophical essays on mind and psychology, Montgomery: Bradford Books

1987 The Intentional Stance, Cambridge, Mass: MIT

1998 Brainchildren, London: Penguin

Dewey, John (1938)

1938 The Theory of Inquiry, New York: Henry Holt and Co

Forbes, Graham

1989 “Biosemantics and the Normative Properties of Thought”, Philosophical Perspectives, vol. 3

Godfrey-Smith, Peter

1996 Complexity and the Function of Mind in Nature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

James, William

1907 Pragmatism: A new name for some old ways of thinking, New York: Longman Green and Co

1911 The Meaning of Truth, New York: Longman Green and Co

Johnston, Mark

1993 “Objectivity Refigured: Pragmatism Without Verificationism” in John Haldane and Crispin Wright (eds.), Reality, Representation and Projection, Oxford: University Press

Miller, Alex

1995 “Objectivity Disfigured: Mark Johnston’s Missing Explanation Argument”, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. LV, no. 4

1997 “More Responses to the Missing Explanation Argument”, Philosophia vol. 25

Millikan, Ruth

1984 Language, Thought, and Other Biological Categories, Cambridge, Mass: MIT, 1984

1993 White Queen Psychology and Other Essays for Alice, Cambridge,

Mass: MIT, 1993

Papineau, David

1990 Truth and Teleology” in Dudley Knowles (ed.) Explanation and Its Limits, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

1993 Philosophical Naturalism, Oxford: Blackwell

Peacocke, Christopher

1992 A Study of Concepts, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Peirce, Charles Sanders

1932 Pragmatism And Pragmaticism: Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce vol 5, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (eds.), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Pietroski, Paul

1992 “Intentionality and Teleological Error”, Philosophical Quarterly vol. 73

Sinclair, Anne

1996 “Young Children’s Practical Deceptions and Their Understanding of False Belief”, New Ideas in Psychology vol. 14, no. 2

Wright, Crispin

1992 “The Euthyphro Contrast” in Truth and Objectivity, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press